This article describes how to transform components of vectors or other tensors between a coordinate basis and an arbitrary frame / tetrad. This process is more general than the transformation between two coordinate bases as found in any introductory general relativity course. Some frames are “non-holonomic” meaning they do not arise from any set of coordinate basis vectors, also there may be situations in which a coordinate representation is inconvenient or not known. I also outline how to implement the transformations in a computer algebra system (CAS).

Effectively we only work in a single tangent space on the manifold, so it turns out to be just a linear algebra problem. My description is based on Carroll (§J) and de Felice & Clarke

(§J) and de Felice & Clarke (§4.2) who assume the frame is orthonormal, however I simply assume it is a basis: that it spans the tangent space and is linearly independent. So suppose we have coordinates

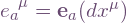

(§4.2) who assume the frame is orthonormal, however I simply assume it is a basis: that it spans the tangent space and is linearly independent. So suppose we have coordinates  , and a frame

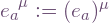

, and a frame  with components

with components  in the coordinate system, that is:

in the coordinate system, that is:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\mathbf e_a = e_a^{\hphantom a\mu}\boldsymbol\partial_\mu\]](http://cmaclaurin.com/cosmos/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-314206c35826278b7a82a65c2b35eb0b_l3.png)

in terms of coordinate basis vectors. I use Latin indices to specify vectors in the tetrad frame, and add a hat for orthonormal frames. I use Greek indices for coordinate components, for example  for the vector

for the vector  . (In place of our

. (In place of our  , de Felice & Clarke write

, de Felice & Clarke write  , and Carroll swaps the index order to

, and Carroll swaps the index order to  .) In a CAS we can implement the frame as a

.) In a CAS we can implement the frame as a  array / matrix called “

array / matrix called “ ” say, reading the indices of

” say, reading the indices of  from left to right but ignoring their up-or-down placement. This ordering conveniently gives an array of “vectors”:

from left to right but ignoring their up-or-down placement. This ordering conveniently gives an array of “vectors”:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\texttt{frame} := \big((e_0^{\hphantom 00},\ldots,e_0^{\hphantom 03}),(\cdots),(\cdots),(\cdots)\big)\]](http://cmaclaurin.com/cosmos/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-9b0d1da1c6f170188457ef54c1775d6b_l3.png)

However there is a tradeoff that vectors are placed in rows instead of the more standard column vector representation, because matrix indices refer to the row first and column second. We also define quantities  implemented as a matrix “

implemented as a matrix “ “, which give the coordinate basis vectors in terms of the new frame:

“, which give the coordinate basis vectors in terms of the new frame:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\partial_\mu = e^b_{\hphantom b\mu}\mathbf e_b\]](http://cmaclaurin.com/cosmos/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-fd5d8885163c6811c9e31d97313a7c7f_l3.png)

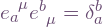

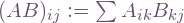

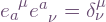

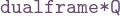

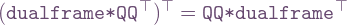

It follows from linear independence that  , hence as matrices:

, hence as matrices:  . The transpose is required because of the index summation order, since the convention for matrix multiplication is

. The transpose is required because of the index summation order, since the convention for matrix multiplication is  . This point could easily be missed when references call it “inverse” with more general index summation in mind. Note summing over the Latin indices also returns the identity:

. This point could easily be missed when references call it “inverse” with more general index summation in mind. Note summing over the Latin indices also returns the identity:  .

.

Now suppose a vector  is specified by its coordinate basis components

is specified by its coordinate basis components  , which we implement as a 4-element array

, which we implement as a 4-element array  . Since

. Since  , substituting the previous expression for

, substituting the previous expression for  and using linear independence gives the components in the new frame (note the Latin index) as:

and using linear independence gives the components in the new frame (note the Latin index) as:  . Programmatically this is the matrix multiplication

. Programmatically this is the matrix multiplication  , at least for my CAS does not distinguish between a row and column vector but automatically matches the dimensions. Now suppose we have

, at least for my CAS does not distinguish between a row and column vector but automatically matches the dimensions. Now suppose we have  different vectors, stored in an

different vectors, stored in an  matrix

matrix  say (typically

say (typically  ). These are processed in a batch operation by converting to column vectors, applying the transformation, then transposing back, so the components are:

). These are processed in a batch operation by converting to column vectors, applying the transformation, then transposing back, so the components are:  , in the new frame.

, in the new frame.

Now consider the dual bases. In the coordinate dual basis, the vector dual to  has components

has components  . These components can be implemented as an array

. These components can be implemented as an array  where

where  is the matrix

is the matrix  and the row / column vector distinction is ignored as before. Again we can lower multiple vectors in one step via

and the row / column vector distinction is ignored as before. Again we can lower multiple vectors in one step via  .

.

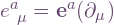

The dual to the new frame satisfies  by definition, hence

by definition, hence

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\mathbf e^b = e^b_{\hphantom b\mu}dx^\mu\]](http://cmaclaurin.com/cosmos/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-0113024ea367c7c5a4c3f6a98147b280_l3.png)

which may be validated by substitution, and these components are just  again. Similarly

again. Similarly

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[dx^\mu = e_a^{\hphantom a\mu}\mathbf e^a\]](http://cmaclaurin.com/cosmos/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-61794e5b27e44def84328cee34b3650f_l3.png)

which are the components  again. Carroll’s description for an orthonormal frame is true for any frame:

again. Carroll’s description for an orthonormal frame is true for any frame:

The vielbeins [ ] thus serve double duty as the components of the coordinate basis vectors in terms of the orthonormal basis vectors, and as components of the orthonormal basis one-forms in terms of the coordinate basis one-forms; while the inverse vielbeins serve as the components of the orthonormal basis vectors in terms of the coordinate basis, and as components of the coordinate basis one-forms in terms of the orthonormal basis.

] thus serve double duty as the components of the coordinate basis vectors in terms of the orthonormal basis vectors, and as components of the orthonormal basis one-forms in terms of the coordinate basis one-forms; while the inverse vielbeins serve as the components of the orthonormal basis vectors in terms of the coordinate basis, and as components of the coordinate basis one-forms in terms of the orthonormal basis.

Likewise Schutz’ (§3.3) description of Lorentz transformations holds more generally:

(§3.3) description of Lorentz transformations holds more generally:

…components of one-forms transform in exactly the same manner as basis vectors and in the opposite manner to components of vectors.

[…Whereas basis one-forms transform] the same as for components of a vector, and opposite that for components of a one-form.

We may also define (de Felice & Clarke, eqn. 4.2.5):

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[e_{a\mu} := \mathbf e_a \cdot \partial_\mu\]](http://cmaclaurin.com/cosmos/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-d7ddeab12780879034acac757f4e2a8c_l3.png)

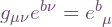

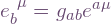

which I interpret as a definition. This evaluates to  (or

(or  ), hence

), hence  . Define also

. Define also

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[e^{b\nu} := \mathbf e^b \cdot dx^\nu\]](http://cmaclaurin.com/cosmos/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-e42c1c2bc57708fb76cfb11fac85c41a_l3.png)

which evaluates to  (or

(or  , where

, where  is the matrix

is the matrix  ), hence

), hence  . Thus Greek indices are raised and lowered in the familiar way — using the metric components in the coordinate basis). On the other hand the metric components in the new frame are

. Thus Greek indices are raised and lowered in the familiar way — using the metric components in the coordinate basis). On the other hand the metric components in the new frame are

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[g_{ab} := \mathbf e_a\cdot\mathbf e_b = g_{\mu\nu}e_a^{\hphantom a\mu}e_b^{\hphantom b\nu}\]](http://cmaclaurin.com/cosmos/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-cc93bb7876fc74444186b4467d222f23_l3.png)

which can be implemented as  . In the particular case of an orthonormal frame

. In the particular case of an orthonormal frame  , so in this case Latin indices are raised and lowered with the Minkowski metric. The metric in the dual frame is

, so in this case Latin indices are raised and lowered with the Minkowski metric. The metric in the dual frame is

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[g^{ab} := \mathbf e^a\cdot\mathbf e^b = g^{\mu\nu}e^a_{\hphantom a\mu}e^b_{\hphantom b\nu}\]](http://cmaclaurin.com/cosmos/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-8063627288b9175a23e5f5e96d9b84a7_l3.png)

so define  . These are matrix inverses:

. These are matrix inverses:  . We can show Latin indices are raised or lowered using this frame metric, so for example

. We can show Latin indices are raised or lowered using this frame metric, so for example  .

.

With all these definitions of components as metric inner products between quantities, we may wonder if the original frame components can also be expressed this way. Indeed they can:  and

and  , where the vectors and dual vectors are acted on one another. The metric is implicit in the summation, because as a (1,1)-tensor it is just the identity. But the (1,1)-tensor

, where the vectors and dual vectors are acted on one another. The metric is implicit in the summation, because as a (1,1)-tensor it is just the identity. But the (1,1)-tensor  made from the “frame” components is also just the identity (see Carroll), so it and the metric tensor are equal. Input

made from the “frame” components is also just the identity (see Carroll), so it and the metric tensor are equal. Input  and

and  into this tensor and it indeed returns

into this tensor and it indeed returns  . We can do similarly with the dual frame.

. We can do similarly with the dual frame.

For higher rank tensors, their components are expressed in the new frame as e.g. (de Felice & Clarke, Hartle  §20.3, §21.2)

§20.3, §21.2)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[T^{ab}_{\hphantom{ab}cd} = T^{\mu\nu}_{\hphantom{\mu\nu}\sigma\tau} e^a_{\hphantom a\mu} e^b_{\hphantom b\nu} e_c^{\hphantom c\sigma} e_d^{\hphantom d\tau}\]](http://cmaclaurin.com/cosmos/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-7324a58c630be7c6d318f3ad0012b23d_l3.png)

My CAS multiplies higher rank “matrices”  by contracting the last index of

by contracting the last index of  with the first index of

with the first index of  . Hence we can only change two indices of

. Hence we can only change two indices of  by this method, short of reordering the indices halfway through. There is another inbuilt method “TensorContract” which I will relate sometime later. Of course you could just program in the sum manually, but I am seeking an elegant solution for aesthetic satisfaction, also because inbuilt operations are probably more optimised. Finally you can continue to mix Greek and Latin (coordinate and frame) indices, see Carroll and I will add an example later.

by this method, short of reordering the indices halfway through. There is another inbuilt method “TensorContract” which I will relate sometime later. Of course you could just program in the sum manually, but I am seeking an elegant solution for aesthetic satisfaction, also because inbuilt operations are probably more optimised. Finally you can continue to mix Greek and Latin (coordinate and frame) indices, see Carroll and I will add an example later.

![]() . This defines a coordinate basis

. This defines a coordinate basis ![]() , where for each

, where for each ![]() the basis vector has components

the basis vector has components![]()

![]() where each dual vector or “1-form” has components

where each dual vector or “1-form” has components![]()

![]()

![]() , we have

, we have ![]() and

and ![]() are not dual in general.

are not dual in general.![]() for some chosen

for some chosen ![]() . This vector has components

. This vector has components ![]() , hence the corresponding 1-form has components

, hence the corresponding 1-form has components ![]() . By the meaning of components this says the 1-form is

. By the meaning of components this says the 1-form is ![]() . This is not

. This is not ![]() , in general! In “musical isomorphism” notation, the result is:

, in general! In “musical isomorphism” notation, the result is:![]()

![]()

![]() to be

to be ![]() . To examine this 1-form, feed it a vector (specifically, basis vectors

. To examine this 1-form, feed it a vector (specifically, basis vectors ![]() ) and see how it acts on it:

) and see how it acts on it:![]()

![]() , as before.

, as before.![]() in general is that the coordinate basis vector

in general is that the coordinate basis vector ![]() is not defined in terms of

is not defined in terms of ![]() alone, but also all the other coordinates chosen. More on that next.

alone, but also all the other coordinates chosen. More on that next. (2009, §3.3, §3.5) makes a superb background to this discussion, and while the cited sections are for special relativity, in this case you can simply replace the Minkowski metric

(2009, §3.3, §3.5) makes a superb background to this discussion, and while the cited sections are for special relativity, in this case you can simply replace the Minkowski metric ![]() with an arbitrary curved metric

with an arbitrary curved metric ![]() .)

.) ). As I emphasise in forthcoming papers, this assumes the static slicing of spacetime, whereas other slicings yield different embedding diagrams. This leads to the question, could we slice flat spacetime in such a way that we get a similar funnel, or mimic other properties of a black hole? While this cannot of course change the fact the 4-dimensional spacetime is flat, the point is there is much flexibility in defining the 3-space, because it depends only on the chosen slicing or observers.

). As I emphasise in forthcoming papers, this assumes the static slicing of spacetime, whereas other slicings yield different embedding diagrams. This leads to the question, could we slice flat spacetime in such a way that we get a similar funnel, or mimic other properties of a black hole? While this cannot of course change the fact the 4-dimensional spacetime is flat, the point is there is much flexibility in defining the 3-space, because it depends only on the chosen slicing or observers.

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[u^\mu = \bigg(\sqrt{1+\frac{2M}{r}},\pm\sqrt\frac{2M}{r},0,0\bigg)\]](http://cmaclaurin.com/cosmos/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-a23830895e20b5289f7a601349e25978_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[-\mathbf u^\flat = \sqrt{1+\frac{2M}{r}}dt \mp\sqrt\frac{2M}{r}dr\]](http://cmaclaurin.com/cosmos/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-e10062edf1c6b99fd63072d04c51a6a6_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[dT := dt \mp\frac{1}{\sqrt{1+r/2M}}dr\]](http://cmaclaurin.com/cosmos/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-d3cc7d754f336fd97d5a8c06c5d08fb1_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ds^2 = -dT^2 \mp \frac{2}{\sqrt{1+r/2M}}dT\,dr + \bigg(1+\frac{2M}{r}\bigg)^{-1}dr^2\]](http://cmaclaurin.com/cosmos/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-dce498983b229b0e27e4e5dceb88a6f8_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[u^\mu = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1-2M/r-r^2\Omega^2}}\big(1, 0, 0, \Omega\big)\]](http://cmaclaurin.com/cosmos/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-bc0d81f26937737baf28bdce20738740_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\frac{1}{\sqrt{1-2M/r-r^2\Omega^2}} \big(r\Omega/\sqrt{1-2M/r},0,0,\sqrt{1-2M/r}/r\big)\]](http://cmaclaurin.com/cosmos/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-c08e37d06c25635c19d1b040857385b6_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\frac{\lvert M-r^3\Omega^2\rvert \sqrt{1-2M/r}}{r^2(1-2M/r-r^2\Omega^2)}\]](http://cmaclaurin.com/cosmos/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-8b0cbd550a3820007fd842efc174ad5a_l3.png)